As the holidays approach, there are the inevitable memes on social media about guests who outstay their welcome.

But we're always glad to have these particular "guests" arrive in our area.

.JPG) |

November 12, 2022

|

Whooping cranes visit our area for short stays during fall and spring migration. In the past several years, their landing sites have been within a couple miles of our house. However, this year, they "booked" a stay a little further west. Our friend, Jim, texted to say that 10 adult cranes and a juvenile were hanging out in our wheat field north of Stafford, so we made a trip to visit.

A small group of cranes that lives and migrates together is called a cohort.

They were a little later than normal. The delay may have been caused by extreme drought and a delayed arrival of colder temperatures.

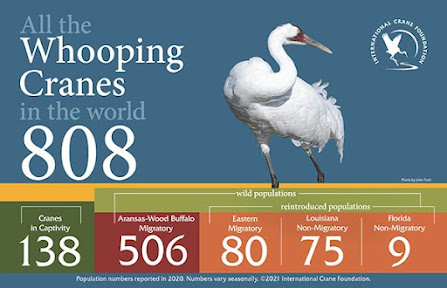

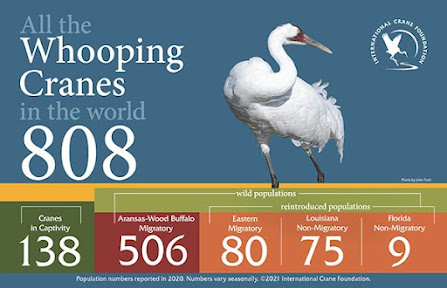

Last year's graphic from the International Crane Foundation reported 802 whooping cranes in the world. This year's graphic was upped to 808. I'm curious whether the juvenile in our field was one of those extra six birds.

My little camera can't

handle that distance, though I gave it the old college try. With a

little creative cropping and enlarging, I got a few mediocre images. (Our sharp-eyed son-in-law noticed other birds in the background of this photo. There was a large grouping of sandhill cranes on our farm ground, too.)

.JPG)

Immature whooping cranes have mottled, brownish-rusty feathers. The adults are bright white birds with accents of red on the head. The legs, bill, and wingtips are black.

The National Wildlife Federation says whooping cranes begin to look for mates and form pair bonds while

they are still at their winter feeding grounds. The pair bonding continues as

they fly to the breeding habitat in the north (the non-migratory

population finds a mate and breeds in the same general location).

.JPG)

At the breeding location, the pair mates and together they build a

nest. They lay one to three eggs (usually two), but normally only one

baby crane survives. Both parents take care of the egg and the young

crane as it develops. The juvenile crane becomes fairly independent

early on, but still receives food from its parents. The juvenile stays

with its parents throughout the first year, including the flight back to

the wintering grounds. They can live above 20 to 25 years in the wild.

.JPG)

After enlarging the photos on my computer, I noticed that some of the adults were banded.

.JPG)

I reported seeing the banded cranes to the National Crane Foundation.

We live near Quivira National Wildlife Refuge. Since whooping cranes are migratory visitors to Quivira, there is a display about them there.

|

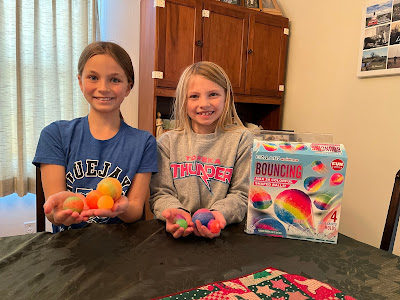

I made this collage from photos taken at Quivira's Education Center in 2013. Kinley and Grandpa were my models at the time. Man, Kinley was so little!

|

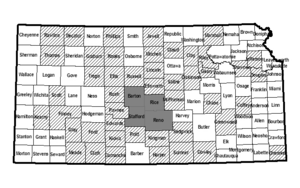

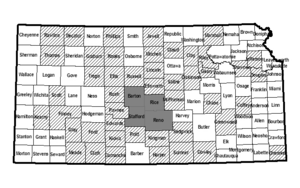

Whooping

Cranes are regular spring and fall transients through our part of Kansas, generally

passing through the marked corridor in March-April and

October-November.

Preferred resting areas are wetlands in level to

moderately rolling terrain away from human activity where low, sparse

vegetation permits ease of movement and an open view. During migration,

cranes feed on grain, frogs, crayfish, grasshoppers, fish, crickets,

spiders, and aquatic plants. (From NWS)

|

Photo from Kim's County Line, 2020

|

Whether I get the "model worthy" photo or not, it's still a

thrill to see them on their migration journey.

.JPG)

Two distinct migratory populations summer in northwestern Canada and

central Wisconsin and winter along the Gulf Coast of Texas and the

southeastern United States, respectively. Those are the cranes that travel through our area. Small, non-migratory

populations live in central Florida and coastal Louisiana.

|

| I

took this photo of whooping cranes in the fall of 2019. We had six that

stayed in our area for several days. |

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)